Measuring The Space Needle

Triangles are awesome, right? Of course. Just ask my daughter Alice what she thinks of triangles, and she’ll tell you: triangles are awesome. Okay, but why? Why are triangles awesome? “Because Vi Hart says so.” Well, yes, but that’s not the only reason.

So Alice and I have spent some time during the summer learning more about triangles. Right now we’re just studying some basic geometry, laying the foundations. But what we’ve covered is still enough to work some cool tricks. Recently, we decided to apply what we’ve learned so far to do something fun:

Measure the Space Needle!

If you’ve studied high school math, then you probably know that this is exactly the sort of task that trigonometry was made for. However, you can still pull off this job without knowing any trigonometry, just relying on some basic geometry facts about similar triangles.

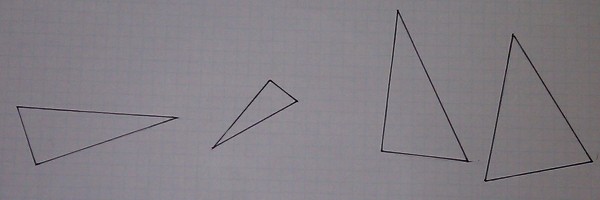

What are similar triangles? Simply put, two triangles are similar if they have the same shape, even if their sizes are different. For example, the triangles on the left are similar, but the triangles on the right are not.

Having the “same shape” is easy to see, but what does it mean exactly? Well, in the case of triangles, what it means is that their angles are all the same.

The neat thing about similar triangles is that the ratios of their sides are also all the same. In other words, if one side of the small triangle is twice as big as the same side of the bigger triangle, then the same is true of the other two sides as well. Or if one pair of sides is six-thirteenths as big, then all the sides are six-thirteenths as big.

We will need one more bit of triangle knowledge, and it’s one of the first things we learn about triangles in school: The three angles of a triangle always add up to 180°. That’s useful because it means that we only have to measure two of a triangle’s three angles. We don't have to directly measure the third one; we can just calculate it.

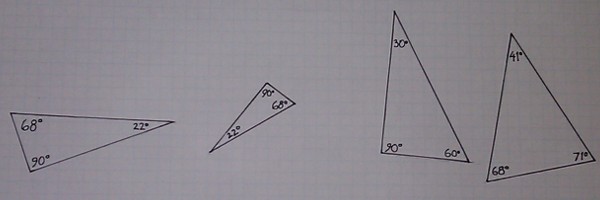

So. Here are the tools we’re going to use to measure the Space Needle.

A protractor, a notebook, and a pen. The protractor includes a ruler 10 centimeters long. That’s the only ruler we’ll be using.

(It may be worth mentioning here that although our notebook has graph lines, we didn’t use them in the measuring process. A notebook of completely blank paper would have worked just as well.)

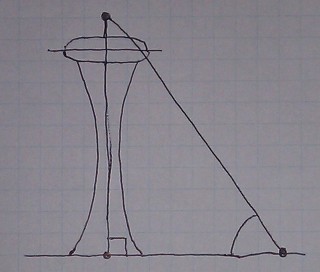

The goal is to construct a triangle in which one side is the Space Needle, from top to bottom, and another side lies completely on the ground, down where we can easily measure it.

Those two sides will naturally form a 90° angle, so we will only need to measure one other angle in order to construct a similar triangle. Naturally, that will be the other angle that’s on the ground.

Oh, but look.

Some of the ground around the Space Needle isn’t entirely flat. There are sloped areas that get in the way. That means we’ll need to do a little extra work to measure the base of our triangle.

(In retrospect, the grounds on the opposite side of the Space Needle are much flatter, and we probably should have done the measurement over there. But it was one of those rare hot summer days in Seattle, and we just gravitated to the shady side without really thinking about it.)

We walked away from the Space Needle until we came up to the EMP building, turned around, and looked up. By chance this was also where the nearby trees ended, giving us a clear view of the top of the Space Needle, so we picked that to be the other end of our triangle’s base.

But there was a catch. We couldn’t see the actual top of the Space Needle: The saucer section is much too big to give us a view of the needle-shaped tip, not without getting much much further away. Alice and I discussed our options, and in the end we decided to measure up to the bottom of the saucer, and then make an educated guess for the remaining height.

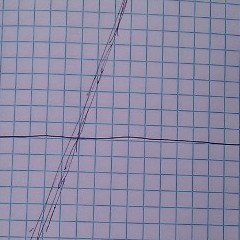

It was time to take our first measurement. First I drew a horizontal line on a blank page of the notebook. Then, Alice stood at our designated spot, and pointed her finger directly at the center of the saucer’s bottom, where the elevator shaft ends. While she did that, I held the notebook up to her arm. Keeping the line I drew as flat as possible, I marked the points where her arm went behind the notebook. Using another page in the notebook as a straightedge, I drew a line connecting the two marks. We now had a record of the angle of our triangle.

Next we needed to measure the base of our triangle. Looking at the grounds, I decided that we would have to break up the measurement into three parts, and do each part separately.

The first part was the distance from where we were standing to where the stairs began.

Alice fixed her eyes on the base of the Space Needle and began walking directly towards it. Of course there were things like pedestrians and poles that prevented us from walking in a perfectly straight line, but she walked as directly as she could manage. I walked with her and counted her footsteps, so she could focus on keeping her stride even and regular. I counted 55 footsteps to the base. We then turned around and walked back. This time I counted 59 footsteps, but Alice had veered near the end, so we discounted that and paced it off a third time. This time I got 56 steps, which was close enough to the first measurement that I felt we could rely on it.

We then started pacing it off a fourth time, but after about a dozen steps I shouted, “Freeze!” Alice stopped, both feet on the ground, and I got down and used the notebook to find the length of her stride, measuring from heel to heel. Her stride came out to two page lengths, plus a little more. I noted the “plus a little more” with a hash mark on the edge of the paper, to be measured later.

Now we had to measure the second part of the base, which was the part on the stairs. If this section had been all stairs, we could have just measured one stair and multiplied by the number of stairs. Unfortunately, it was a mixture of stairs and flat areas.

So instead Alice calibrated her footsteps on the flat landings to be the same horizontal distance as when she was on the stairs. It was a little tricky, but we did our best and got a distance of 25 footsteps. This stride was a little over a single notebook page long, and again I marked the extra amount on the edge of a page.

Finally, we had to measure the last part of the distance, namely the length from the head of the stairs to the middle of the Space Needle’s base.

However, the bottom part of the Space Needle is occupied by a building, and you need to buy a ticket in order to go in. So we needed to measure this part indirectly. After considering a couple of approaches, Alice and I decided to take advantage of the fact that the area around the Space Needle was circular, and measure its circumference. Our distance would then be the radius of this circle. I liked this approach because any errors in our measurement would be scaled down by a factor of 2 pi (or tau, for those in the know), meaning that our measurement would probably be pretty accurate despite having to follow a curved path. Alice liked this approach because it involved using pi.

The immediate area around the Space Needle actually slopes up as it goes around, so that when you come around again you’re exactly one story higher. But the slope was gentle enough compared to the distance involved that I figured it wouldn’t be significant enough to ruin our measurement. Our pacing took us right up to the second-floor entrance, for a total of 242 footsteps. “Sorry, we’re not going in,” I explained to the man at the door collecting tickets. “We’re just measuring.”

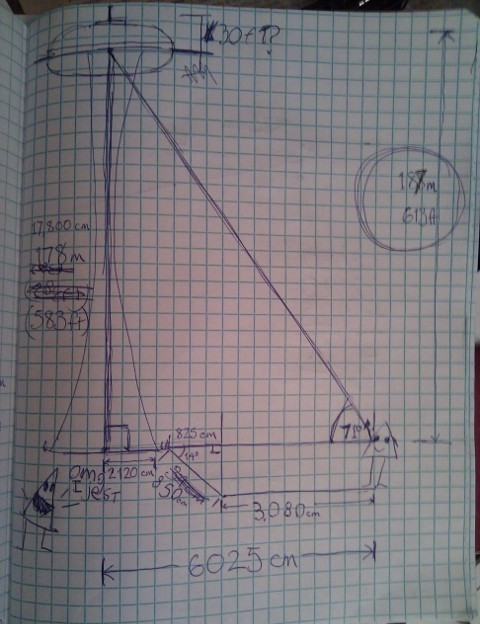

With that, we had all the numbers that we needed. We quickly retreated out of the hot sun to the Armory to get something cool to drink and do our calculations. The Armory was currently hosting a Polish Festival, and there was an appropriately energetic band playing live music as we worked. I drew a new diagram that showed the piecemeal measurements of our base, and then we pulled out the protractor.

It was time to measure things!

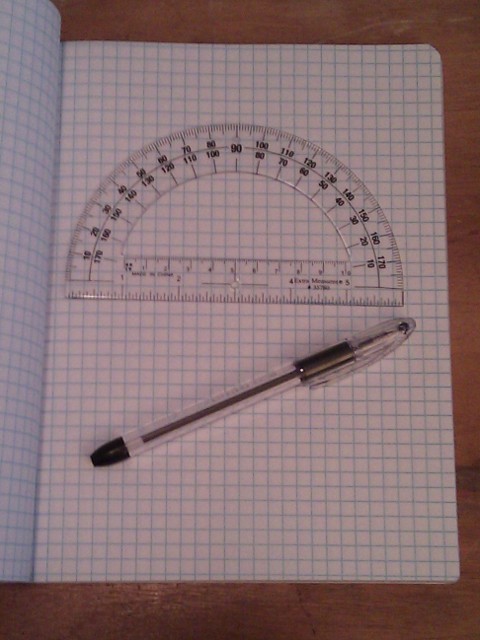

The first thing to measure was the angle of our triangle.

The protractor showed us that our angle came out to 71°.

Now we needed the measure the three parts that made up the base of our triangle.

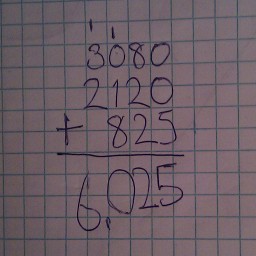

To measure the first part, we needed to know the size of Alice’s footsteps. Using the 10-centimeter ruler on the protractor, we measured the height of the notebook paper as being 24¼ cm. The extra length that I had marked on the page came out to 6½ cm, so that plus two notebook pages gave us a total of 55 centimeters per footstep. Multiplying that by 56 footsteps reveals a measurement of 3080 cm for the first section of the triangle’s base.

For the middle section, we measured Alice’s stair-step stride as 33 cm, so multiplying that times 25 footsteps gave us 825 cm.

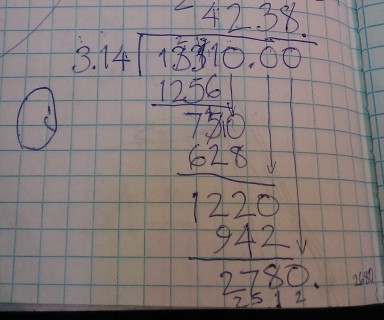

For the third section, we’re back to using Alice’s normal stride of 55 cm per footstep, and multiplying that by 242 footsteps gave us a whopping 13310 cm for the circumference of the circle around the base of the Space Needle. Now we needed to use the circumference to determine the radius. Time for some long division.

The result of dividing by pi gave us 4239 cm for the diameter, and taking half of that gave us 2119½ cm for the radius, which we rounded up to 2120 cm. We could now add all three sections together.

At last, we had the length of our triangle’s base: 6025 cm.

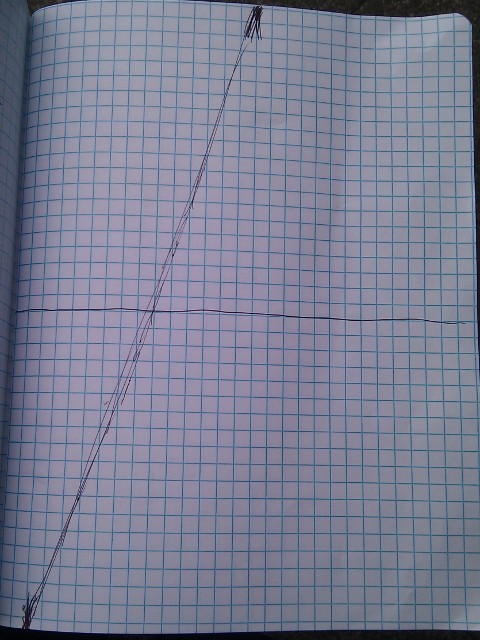

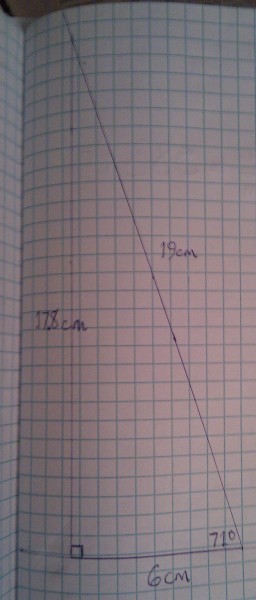

Now, here is where the power of similar triangles comes in. On a fresh page in the notebook, we drew a line 6 cm long, because 6 cm is very close to being a thousandth (1/1000) of the size of the base of our big triangle. We then used the protractor to make a 90° angle on one end, and a 71° angle on the other end. Then we extended the lines for these angles upwards until they met (just before they ran off the top of the page).

And there it was: a similar triangle that was 1000 times smaller than the Space Needle. We carefully measured the triangle’s perpendicular side and got a length of 17.8 cm.

(We also measured the hypotenuse of our triangle so it wouldn’t feel left out.)

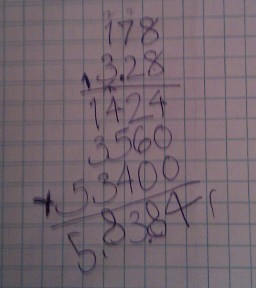

Multiplying 17.8 cm by 1000 equals 17800 cm, or 178 meters. So that’s the size that we calculated for the Space Needle. It was time to check our work, to see how close we came to the real number. But wait! Alice wanted to have our estimated height converted to feet before we looked at the answer. Unfortunately, I couldn’t remember the exact conversion for meters to feet, only that it was 3-something. After some discussion, we agreed it would be okay to briefly go online and look up the conversion factor, as long as we still did the actual conversion ourselves, on paper. So we did, and found that one meter equals 3.28 feet. We worked through the long multiplication together, and got 583.84 feet.

Time to check our work. No, wait! We had completely forgotten about the saucer section. We still had to estimate its height and add that to our total. Going on our vague memories of what the top of the Space Needle contained, we decided that it was probably close to 3 stories tall, or about 9 meters. That put our final number, our estimate for the full height of the Space Needle, at 187 meters, or 613 feet.

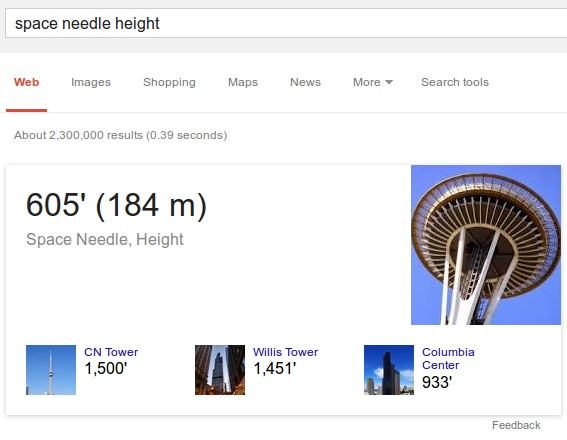

NOW it was time to check our work. Feeling a bit nervous, I hopped back online and did a web search:

Success!

(In actual fact, the top part of the Space Needle is much larger than 9 meters. It was coincidental that the underestimate in our guess for the saucer so closely matched the overestimate in our measurement for the tower.)

Even though a lot of luck was involved in getting that close to the correct answer, I felt that we had ample cause to be smug. Alice agreed that it would have been hard to overstate her satisfaction. We danced out of the Armory to the strains of a sprightly mazurka, and headed to the bus stop in search of some celebratory frozen yogurt.

And that is one of the many reasons why triangles are awesome.